Tsunami modeling

The phenomenon of a tsunami is often modeled using shallow water equations. During a tsunami, the waves have a very small amplitude compared to the wavelength (typically around 100 km or more ) and the depth of the ocean. However, as they approach the coast/surface, the ocean’s depth reduces, and so does the wavelength. These systems can be modeled as a hyperbolic system of partial differential equations.

The numerical methods require the ability to capture shocks. They are based on extensions of the Godunov method. They are used to solve Riemann problems at the interfaces between grid cells. The second-order corrections terms are defined using limiters to avoid non-physical oscillations. Further on, mass conservation near the shore is challenging due to adaptive mesh refinement.

Modeling tools and features

There have been several tools that have been used to date. Some of the noteworthy ones being

GeoClaw is a package available as a part of Clawpack [LeGeBe2011] , [Beetal2011] . The primary goal of Clawpack software is to solve hyperbolic PDEs and has an adaptive mesh refinement strategy encoded. It can be downloaded from GeoClaw. In the upcoming sections, we will discuss how to build the software and run related examples.

AMROC is another package that is well known for adaptive meshing. It is written in C++ and also incorporates Clawpack. Overall, the software seems to have better documentation. It can be downloaded from AMROC website.

OpenFOAM is an open/source CFD solver that is used extensively. It was also recently used to simulate Tsunami [Xietal2018].

Chombo is another platform that facilitates automated meshing and can be downloaded from the official Chombo website.

SAMRAI can be downloaded from the official website.

FLASH was initially developed for simulation of gas dynamics in astrophysics applications. It can be downloaded from the Stony Brook University website.

The simulation of tsunami events requires several modeling considerations. To start with, the free surface flow problem needs to be considered. When the free surface is considered, then the tangential shear vanishes.

During each time step, the location of the wet and dry interfaces needs to be computed at each step. This involves moving boundaries. Tracking a moving boundary is complex, and most codes do not account for this. The shoreline topology constantly changes with islands and isolated lakes appearing and disappearing. Most codes consider solid wall boundary to measure the depth at that point and convert it to inundation distances via empirical measures.

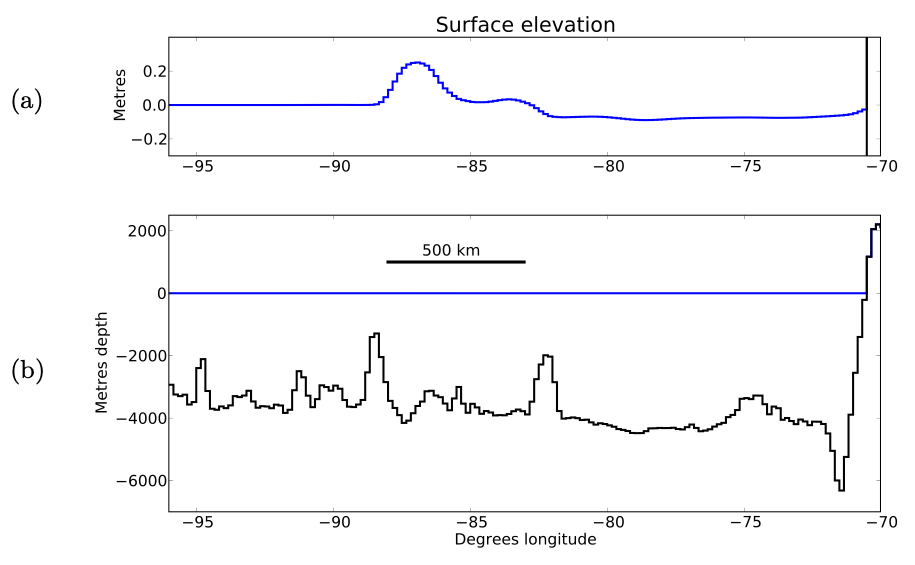

It is further necessary to capture small perturbations to the undisturbed water at rest. Consider here that the ocean is about 4 km deep. In comparison, tsunami wave amplitude is 1m in the open sea, and wavelength is about 100 km. Considering this, over 1 km, the tsunami varies by less than 1 cm. In addition, the bathymetry may differ by 100’s of meters. Thus, it is required that a stable numerical method is required to maintain a steady-state of the ocean at rest to accurately capture the small perturbations. An example of the same is shown below.

Fig. 3.1.8 C/S of Pacific Ocean at 25-deg S. Zoom of surface elevation from -20 to 20 cm showing the small amplitude and long wavelength of a tsunami (after 2.5 h of an earthquake) (TOP). Full-depth of the ocean (BOTTOM)

It is necessary to use a “wetting-drying” algorithm. Here, the computational grid covers dry land and the ocean. Each grid is allowed to be wet \(\left(h > 0\right)\) or dry \(\left(h = 0\right)\) in the shallow water equations. The state of each cell is updated dynamically as the wave advances or retreats. Accurate modeling requires detailed models of local topography. The mesh resolution needs to be of the order of 10’s of meters.

References

LeVeque and D. L. George and M. J. Berger, “Tsunami modelling with adaptively refined finite volumen methods,” Acta Numerical, vol. 20, pp. 211 - 289 (2011)

Berger and D. L. George and R. J. LeVeque and K. L. Mandli, “The GeoClaw software for depth-averaged flows with adaptive refinement,” Advances in Water Resources, vol. 34, pp. 1195 - 1206 (2011)

Qin and M. R. Motley and N. A. Marafi, “Three-dimensional modeling of tsunami forces on coastal communities,” Coastal Engineering, vol. 140, pp. 43 - 59 (2018)