2. The Pelicun Framework

2.1. Abbreviations

- BIM:

Building Information Model

- DL:

Damage and Loss

- EDP:

Engineering Demand Parameter

- EVT:

Hazard Event (of earthquake/tsunami/storm surge hazard)

- GM:

Ground Motion (of earthquake hazard)

- IM:

Intensity Measure (of hazard event)

- SAM:

Structural Analysis Model (i.e. finite element model)

- SIM:

Simulation

- UQ:

Uncertainty Quantification

- RV:

Random Variables

- QoI:

Quantities of Interest

- DS:

Damage State

- DV:

Decision Variable

- LS:

Limit State

2.2. Introduction to Pelicun

Pelicun is an open-source Python package released under a 3-Clause BSD license (see Copyright and license). It can be used to conduct natural hazard risk analyses. That is, to quantify damage and losses from a natural hazard scenario. Applications can range from a simple and straightforward use of a vulnerability function to model the performance of an entire asset to detailed high-resolution evaluations involving the individual components it is comprised of. Spatial scales can span form a single asset to portfolio-level evaluations involving thousands of assets.

Pelicun implements state of the art approaches to natural hazards risk estimation, and as such, is rooted in probabilistic methods. Common steps of an assessment using Pelicun include the following:

Describe the joint distribution of demands or asset response. The response of a structure or other type of asset to natural hazard event is typically described by so-called engineering demand parameters (EDPs). Pelicun provides various options to characterize the distribution of EDPs. It can calibrate a multivariate distribution that describes the joint distribution of EDPs if raw EDP data is available. Users can control the type of each marginal distribution, apply truncation limits to the marginal distributions, and censor part of the data to consider detection limits in their analysis. Alternatively, Pelicun can use empirical EDP data directly, without resampling from a fitted distribution.

Define a performance model. The fragility and consequence functions from the first two editions of FEMA P-58 and the HAZUS earthquake and hurricane wind and storm surge models for buildings are provided with Pelicun. This facilitates the creation of performance models without having to collect and provide component descriptions and corresponding fragility and consequence functions. An auto-population interface encourages researchers to develop and share rulesets that automate the performance-model definition based on the available building information. Example scripts for such auto-population are also provided with the tool.

Simulate asset damage. Given the EDP samples, and the performance model, Pelicun efficiently simulates the damages in each component of the asset and identifies the proportion of realizations that resulted in collapse.

Estimate the consequences of damage. Using information about collapse and component damages, the following consequences can be estimated with Pelicun: repair cost and time, unsafe placarding (red tag), injuries of various severity and fatalities.

2.3. Overview

The conceptual design of the Pelicun framework is modeled after the FEMA P-58 methodology, which is generalized to provide a flexible system that can accommodate a large variety of damage and loss assessment methods. In the following discussion, we first describe the types of performance assessment workflows this framework aims to support; then, we explain the four interdependent models that comprise the framework.

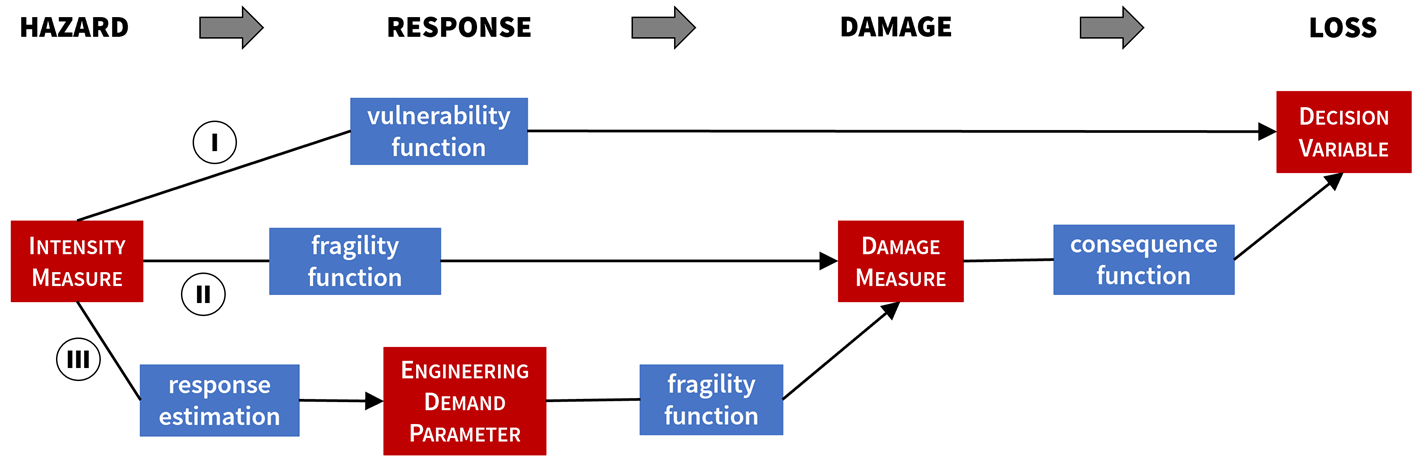

Loss assessment in its most basic form requires the characterization of the seismic hazard as input and aims to provide an estimate of the consequences, or losses, as output. Using the terminology of FEMA P-58, the severity of the seismic hazard is quantified with the help of intensity measures (IMs). These are characteristic attributes of the ground motions, such as spectral acceleration, peak ground acceleration, or peak ground velocity. Consequences are measured by decision variables (DVs). The most popular DVs are repair cost, repair time, and the number of injuries and fatalities. Fig. 2.1 shows three different paths, or performance assessment workflows, from IM to DV:

The most efficient approach takes a single, direct step using vulnerability functions. Such vulnerability functions can be calibrated for broad classes of buildings (e.g. single-family wooden houses) using ground motion intensity maps and insurance claims data from past earthquakes. While this approach allows for rapid calculations, it does not provide information about structural response or damage.

The second approach introduces damage measures (DMs), which classify damages into damage states (DSs). Each damage state represents a set of potential damages to a structure, or structural component, that require similar kinds and amounts of repair effort. Given a database of IMs and corresponding DMs after an earthquake, fragility functions can be calibrated to describe the relationship between them. The more data is available, the more specialized (i.e., specific to particular types of buildings) fragility functions can be developed. The second step in this path uses consequence functions to describe losses as a function of damages. Consequence functions that focus on repairs can be calibrated using cost and time information from standard construction practice—a major advantage over path I considering the scarcity of post-earthquake repair data.

The third path introduces one more intermediate step: response estimation. This path envisions that the response of structures can be estimated, such as with a sophisticated finite element model, or measured with a structural health monitoring system. Given such data, damages can be described as a function of deformation, relative displacement, or acceleration of the structure or its parts. These response variables, or so-called engineering demand parameters (EDPs), are used to define the EDP-to-DM relationships, or fragility functions. Laboratory tests and post-earthquake observations suggest that EDPs are a good proxy for the damages of many types of structural components and even entire buildings.

Fig. 2.1 Common workflows for structural performance assessment.

The functions introduced above are typically idealized relationships that provide a probabilistic description of a scalar output (e.g., repair cost as a random variable) as a function of a scalar input. The cumulative distribution function and the survival function of Normal and Lognormal distributions are commonly used in fragility and vulnerability functions. Consequence functions are often constant or linear functions of the quantity of damaged components. Response estimation is the only notable exception to this type of approximation, because it is regularly performed using complex nonlinear models of structural behavior and detailed time histories of seismic excitation.

Uncertainty quantification is an important part of loss assessment. The uncertainty in decision variables is almost always characterized using forward propagation techniques, Monte Carlo simulation being the most widely used among them. The distribution of random decision variables rarely belongs to a standard family, hence, a large number of samples are needed to describe details of these distributions besides central tendencies. The simulations that generate such large number of samples at a regional scale can demand substantial computational resources. Since the idealized functions in paths I and II can be evaluated with minimal computational effort, these are applicable to large-scale studies. In path III, however, the computational effort needed for complex response simulation is often several orders of magnitude higher than that for other steps. The current state of the art approach to response estimation mitigates the computational burden by simulating at most a few dozen EDP samples and re-sampling them either by fitting a probability distribution or by bootstrapping. This re-sampling technique generates a sufficiently large number of samples for the second part of path III. Although response history analyses are out of the scope of the Pelicun framework, it is designed to be able to accommodate the more efficient, approximate methods, such as capacity spectra and surrogate models. Surrogate models of structural response (e.g., [11]) promise to promptly estimate numerical response simulation results with high accuracy.

Currently, the scope of the framework is limited to the simulation of direct losses and the calculations are performed independently for every building. Despite the independent calculations, the Pelicun framework can produce regional loss estimates that preserve the spatial patterns that are characteristic to the hazard, and the built environment. Those patterns stem from (i) the spatial correlation in ground motion intensities; (ii) the spatial clusters of buildings that are similar from a structural or architectural point of view; (iii) the layout of lifeline networks that connect buildings and heavily influence the indirect consequences of the disaster; and (iv) the spatial correlations in socioeconomic characteristics of the region. The first two effects can be considered by careful preparation of inputs, while the other two are important only after the direct losses have been estimated. Handling buildings independently enables embarrassingly parallel job configurations on High Performance Computing (HPC) clusters. Such jobs scale very well and require minimal additional work to set up and run on a supercomputer.

2.4. Performance Assessment Workflow

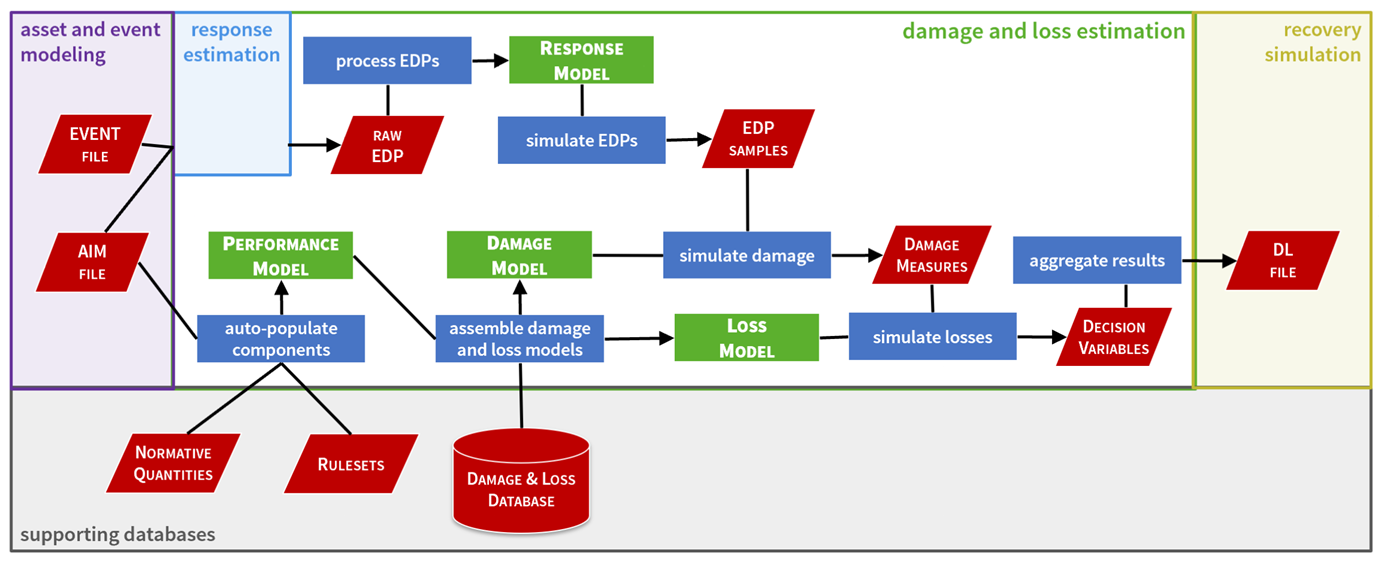

Fig. 2.2 introduces the main parts and the generic workflow of the Pelicun framework and shows how its implementation connects to other modules in the SimCenter Application Framework. Each of the four highlighted models and their logical relationship are described in more detail in Fig. 2.3.

Fig. 2.2 The main components and the workflow of the Pelicun framework.

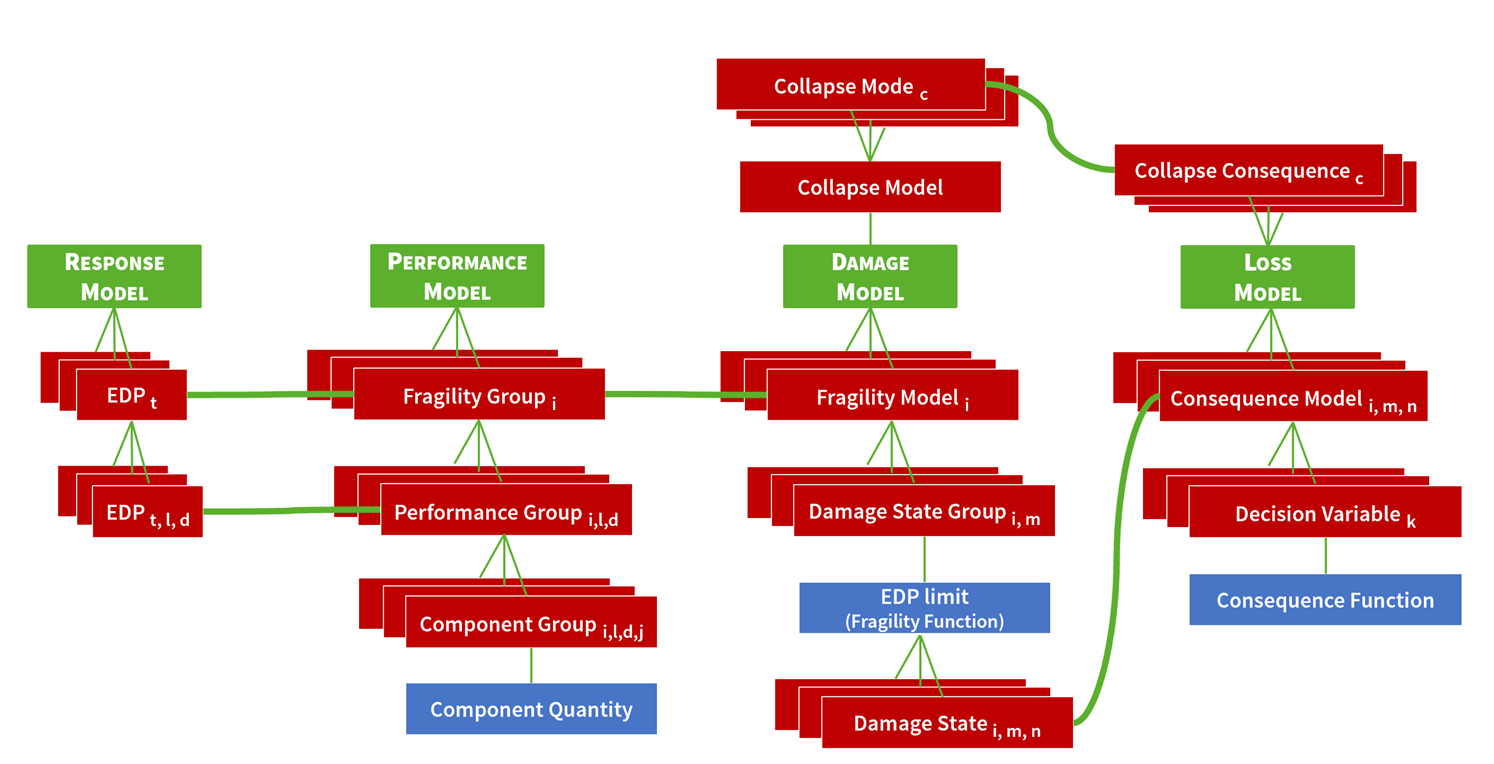

Fig. 2.3 The four types of models and their logical relationships in the Pelicun framework.

The calculation starts with two files: the Asset Information Model (AIM) and the EVENT file. Currently, both files are expected to follow a standard JSON file format defined by the SimCenter. Support of other file formats and data structures only require a custom parser method. The open source implementation of the framework can be extended by such a method and the following part of the calculation does not require any further adjustment. AIM is a generalized version of the widely used Building Information Model (BIM) idea and it holds structural, architectural, and performance-related information about an asset. The word asset is used to emphasize that the scope of Pelicun is not limited to building structures. The EVENT file describes the characteristic seismic events. It typically holds information about the frequency and intensity of the event, such as its occurrence rate or return period, and corresponding ground motion acceleration time histories or a collection of intensity measures.

Two threads run in parallel and lead to the simulation of damage and losses: (a) response estimation, creating the response model, and simulation of EDPs; and (b) assembling the performance, damage, and loss models. In thread (a), the AIM and EVENT files are used to estimate the response of the asset to the seismic event and characterize it using EDPs. Peak interstory drift (PID), residual interstory drift (RID), and peak floor acceleration (PFA) are typically used as EDPs for building structures. Response simulation is out of the scope of Pelicun; it is either performed by the response estimation module in the Application Framework (Fig. 1) or it can be performed by any other application if Pelicun is used outside of the scope of SimCenter. The Pelicun framework can take advantage of response estimation methods that use idealized models for the seismic demand and the structural capacity, such as the capacity curve-based method in HAZUS or the regression-based closed-form approximation in the second edition of FEMA P-58 vol. 5 [12]. If the performance assessment follows path I or II from Fig. 2.1, the estimated response is not needed, and the relevant IM values are used as EDPs.

2.5. Response Model

The response model is based on the samples in the raw EDP file and provides a probabilistic description of the structural response. The samples can include an arbitrary number of EDP types (EDPt in Fig. 4) that describe the structural response at pre-defined locations and directions (EDPt,l,d). In buildings, locations typically correspond to floors or stories, and two directions are assigned to the primary and secondary horizontal axes. However, one might use more than two directions to collect several responses at each floor of an irregular building and locations can refer to other parts of structures, such as the piers of a bridge or segments of a pipeline.

EDPs can be resampled either after fitting a probability distribution function to the raw data or by bootstrapping the raw EDPs. Besides the widely used multivariate lognormal distribution, its truncated version is also available. This allows the consideration, for example, that PID values above a pre-defined truncation limit are not reliable. Another option, using the raw EDPs as-is, is useful in regional simulations to preserve the order of samples and maintain the spatial dependencies introduced in random characteristics of the building inventory or the seismic hazard.

2.6. Performance Model

Thread (b) in Fig. 3 starts with parsing the AIM file and constructing a performance model. If the definition in the file is incomplete, the auto-populate method tries to fill the gaps using information about normative component quantities and pre-defined rulesets. Rulesets can link structural information, such as the year of construction, to performance model details, such as the type of structural details and corresponding components.

The performance model in Pelicun is based on that of the FEMA P-58 method. It disaggregates the asset into a hierarchical description of its structural and non-structural components and contents (Fig. 4):

Fragility Groups (FGs) are at the highest level of this hierarchy. Each FG is a collection of components that have similar fragility controlled by a specific type of EDP and their damage leads to similar consequences.

Each FG can be broken down into Performance Groups (PGs). A PG collects components whose damage is controlled by the same EDP. Not only the type of the EDP, but its location and direction also has to be identical.

In the third layer, PGs are broken down into the smallest units: Component Groups (CGs). A CG collects components that experience the same damage (i.e., there is perfect correlation between their random Damage States). Each CG has a Component Quantity assigned to it that defines the amount of components in that group. Both international standard and imperial units are supported as long as they are consistent with the type of component (e.g., m2, ft2, and in2 are all acceptable for the area of suspended ceilings, but ft is not.) Quantities can be random variables with either Normal or Lognormal distribution.

In performance models built according to the FEMA P-58 method, buildings typically have FGs sensitive to either PID or PFA. Within each FG, components are grouped into PGs by stories and the drift-sensitive ones are also grouped by direction. The damage of acceleration-sensitive components is based on the maximum of PFAs in the two horizontal directions. The Applied Technology Council (ATC) provides a recommendation for the correlation between component damages within a PG. If the damages are correlated, all components in a PG are collected in a single CG. Otherwise, the performance model can identify an arbitrary number of CGs and their damages are evaluated independently.

The Pelicun framework handles the probabilistic sampling for the entire performance model with a single high-dimensional random variable. This allows for custom dependencies in the model at any level of the hierarchy. For example, one can assign a 0.8 correlation coefficient between the fragility of all components in an FG that are on the same floor, but in different directions and hence, in different PGs. In another example, one can assign a 0.7 correlation coefficient between component quantities in the same direction along all or a subset of floors. These correlations can capture more realistic exposure and damage and consider the influence of extreme cases. Such cases are overlooked when independent variables are used because the deviations from the mean are cancelling each other.

This performance model in Fig. 4 can also be applied to more holistic description of buildings. For example, to describe earthquake damage to buildings following HAZUS, three FGs can handle structural, acceleration-sensitive non-structural, and drift-sensitive non-structural components. Each FG has a single PG because HAZUS uses building-level EDPs—only one location and direction is used in this case. Since components describe the damage to the entire building, using one CG per PG with “1 ea” as the assigned, deterministic component quantity is appropriate.

The performance model in Pelicun can facilitate filling the gap between the holistic and atomic approaches of performance assessment by using components at an intermediate resolution, such as story-based descriptions, for example. These models are promising because they require less detailed inputs than FEMA P-58, but they can provide more information than the building-level approaches in HAZUS.

2.7. Damage Model

Each Fragility Group in the performance model shall have a corresponding fragility model in the Damage & Loss Database. In the fragility model, Damage State Groups (DSGs) collect Damage States (DSs) that are triggered by similar magnitudes of the controlling EDP. In Pelicun, Lognormal damage state exceedance curves are converted into random EDP limits that trigger DSGs. When multiple DSGs are used, assuming perfect correlation between their EDP limits reproduces the conventional model that uses exceedance curves. The approach used in this framework, however, allows researchers to experiment with partially correlated or independent EDP limits. Experimental results suggest that these might be more realistic representations of component fragility. A DSG often has only a single DS. When multiple DSs are present, they can be triggered either simultaneously or they can be mutually exclusive following the corresponding definitions in FEMA P-58.

2.8. Loss Model

Each Damage State has a corresponding set of consequence descriptions in the Damage & Loss Database. These are used to define a consequence model that identifies a set of decision variables (DVs) and corresponding consequence functions that link the amount of damaged components to the value of the DV. The constant and quantity-dependent stepwise consequence functions from FEMA P-58 are available in Pelicun.

Collapses and their consequences are also handled by the damage and the loss models. The collapse model describes collapse events using the concept of collapse modes introduced in FEMA P-58. Collapse is either triggered by EDP values exceeding a collapse limit or it can be randomly triggered based on a collapse probability prescribed in the AIM file. The latter approach allows for external collapse fragility models. Each collapse mode has a corresponding collapse consequence model that describes the corresponding injuries and losses.

Similarly to the performance model, the randomness in damage and losses is handled with a few high-dimensional random variables. This allows researchers to experiment with various correlation structures between damages of components, and consequences of those damages. Among the consequences, the repair costs and times and the number of injuries of various severities are also linked; allowing, for example, to consider that repairs that cost more than expected will also take longer time to finish.

Once the damage and loss models are assembled, the previously sampled EDPs are used to evaluate the Damage Measures (Fig. 3). These DMs identify the Damage State of each Component Group in the structure. This information is used by the loss simulation to generate the Decision Variables. The final step of the calculation in Pelicun is to aggregate results into a Damage and Loss (DL) file that provides a concise overview of the damage and losses. All intermediate data generated during the calculation (i.e., EDPs, DMs, DVs) are also saved in CSV files.